For rigorous teachers seized my youth

And purged its flame and trimmed its fire

Showed me the high white star of truth

There bade me gaze, and there aspire

- Matthew Arnold, Stanzas from the Grand Chartreuse

Please enjoy this month’s free article!

There are many of us today who call ourselves religious, or believe in the “spiritual,” nevertheless, society tends to neglect this spiritual dimension and therefore makes itself vulnerable to malicious spiritual manipulation. Not all that is spiritual is good. Most social problems are, at root, spiritual ones.

The New Romantic Movement is a new way of thinking through how we may address these spiritual problems without devolving into the simplistic dichotomy of bipartisan politics. Left and Right are simply not useful categories when thinking about Good and Evil because there is a little of both in each.

A Longing for the Past

Romanticism is an artistic movement that began in Western Europe in the 1800s and flourished into the mid 1900s. It was an art movement that emphasised imagination, emotion and the subjective experience. In many ways, it defined our modern understanding of the functions and objectives of art today. It emerged as a response to a disillusionment with Enlightenment values of reason and rationality as being incomplete imperatives that could not explain the mystical and unmeasurable dimensions of the human spirit.

“Romanticism is situated neither in choice of subject, nor in exact truth but rather, in a way of feeling.”

Charles Baudelaire, 1846

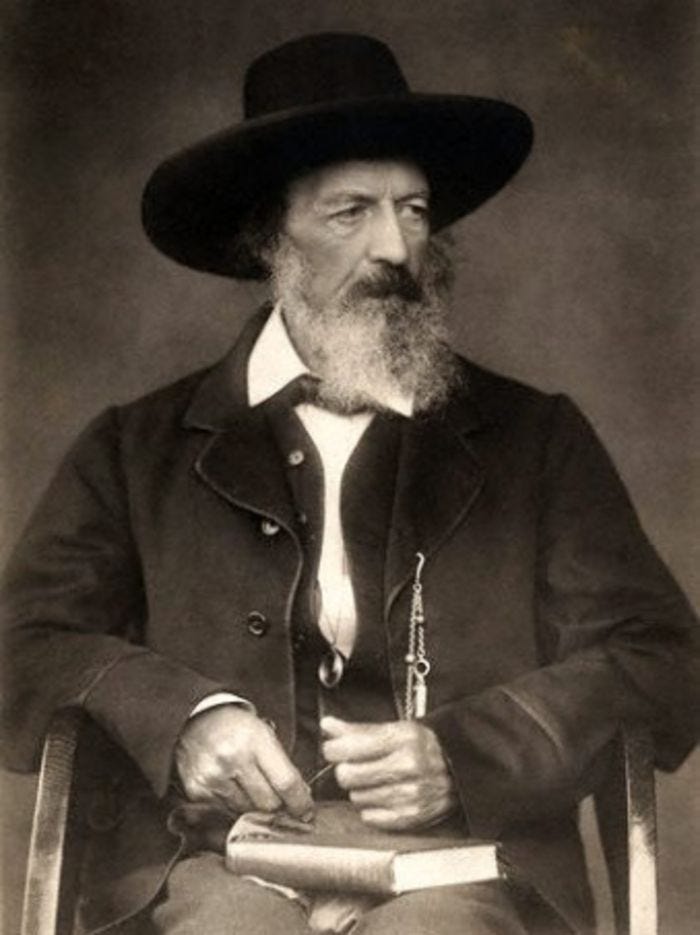

The word Romance, however, finds its origins in the fifth century. A romance was any story told in the latin or latin-derivative language and was mainly used in France. These stories were typically about chivalric knights going on grand adventures. This is why all latin based languages today are also called “romance languages” such as Italian, French, Portuguese and Spanish. In the nineteenth century, artists, poets and thinkers had a longing for the medieval era when a belief in God was a given and the matters of the soul were just as, if not more important than, matters of the material world. We can see this in the poetry of Alfred Lord Tennyson for example, when he writes In Memoriam.

Be near me when my faith is dry,

And men the flies of latter spring,

They lay their eggs, and sting and sing

And weave their petty cells and die.

(Canto 50)

Tennyson is confronted with complex existential questions when his best friend, Arthur Hallum, tragically dies at the age of just twenty-two. His poem describes the way in which he wrestles to reconcile his faith in God with the scientific advancements of the 19th century that would negate the basic tenets of his faith. Darwin’s Theory of Evolution had, at this time, called into question the idea that all human life was divinely created and there was a heaven awaiting mankind after death.

Tennyson, therefore, laments in his poem about the lack of consolation one may derive from faith in God if one is to accept the scientific ideas of the time. This existential conflict is emblematic of greater conflicts during this time between material rationality and faith: what are the ends to which we may endeavour? Is virtue a “practical” end to aspire to at all? Is vice justified where it is practical? I personally of course argue that matters of “practicality” are thinly concealed avarice anyway.

The collecting of material wealth can do nothing for the soul and we have more than a century of evidence before us of the hollowing out of the human spirit that results when we abandon God for this “practicality”. But Tennyson was asking these questions at the dawn of this era. Tennyson’s elegy for his dead friend, was also an elegy for an era of easy, child-like faith. Everyone is not equipped to question their faith and come out of it unscathed by the claws of evil that opportunistically prey upon a soul weakened by doubt.

In literature, Romanticism deals with imagination, devotion to beauty, fascination with nature, individualism, and a fascination with the past and its myths. This was a time period when human rights were being codified, implying that the collective unconscious began to appreciate the individual as separate from the collective. Psychology as a subject would soon be explored by people like Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung as people began to examine their own personal psychological dramas separately from others. It is against this backdrop of new-found individualism and sovereignty, against myth and the chaos of nature, that the Romantics created with a fire and a fury.

“It was a life of haste, so full that they had no time to reflect where we have been and whither we intend to go...still less the value and the purpose and price of what we have seen, done and visited”.

William Rathbone Greg, “Life at High Pressure” (1875)

This quote above by William Rathbone Greg is as relevant today as it was in the era that wrote it down. The Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed the architecture of human society and as a consequence, the human psyche as well. We all believed that if we could communicate with each other more quickly, we might be able to have more time in the day; however, all that really happened was that we factored in this speed and our schedules became more packed. We began to expect things to be done faster and faster. Rather than give us more time, technology took away more of it. Where once we had time to spend weeks knitting and sewing clothes by hand, the technology to make clothes more quickly has paradoxically given us less time.

The dangerous consequence, of course, of such rushing, is that we also have less time to reflect whether our lives are going the way we want them to--whether the place we are rushing to is where we really want to go. At the risk of condemnation for repeating a cliche--life is about the journey and we are increasingly automating away the journey in every way, robbing us of this crucial dimension of the pleasure of life itself. For what? Gosh, many of us don’t even have time to think about that question. Maybe do your dishes by hand tonight, without having a podcast or music on in the background, so you can ask it of yourself and actually listen to the answer your heart provides.

A Longing for the Human

Digital technology pervades every dimension of existence today. Although technology is as human as having opposable thumbs--we have invented and used technology as long as humanity has existed--digital technology is a new phenomenon that distinguishes the modern age with its lack of physicality. Digital technology abandons all physical knowledge for cerebral knowledge. We can send ideas at the speed of light but the material things still take just as much time. We can create simulations of relationships, experiences, people, and money, but in doing so, the real things lay gathering dust, untended outside “away from keyboard”.

But there is a shift happening. There is increasingly a feeling of un-ease with this digital world. We crave real tickets we can hold in our hands instead of QR codes. We want menus we can touch, not touch-screens. We want buttons and cranks. We want to make physical things. We are realising that we don’t look at our family photos when they remain digital. Books that we physically keep can’t be effaced or changed by malignant government censorship. Live music. Art made of real paint and ink. We look for the wabi-sabi mistakes of the human handprint in everything. We don’t want to live in the matrix. We don’t want to die and become so many pixels in the metaverse.

The New Romantic Movement therefore takes its nostalgia from the 19th century movement and expands upon it to articulate what it was that our precursors, Tennyson, Keats, Arnold, Wordsworth were all presciently warning us about: we want to preserve the human in an increasingly inhuman world. To feel alive we need a physicality not only a mentality.

This explains why there is currently also an explosion of new-found faith in Catholicism and Eastern Orthodox Christianity as both sects emphasise the importance of the physical elements of ritual and religion. The material, so important to the secularists, has hitherto been desecrated by the religious; if the religious understand the importance of the material and give it its proper importance, perhaps the secular will have less of a hold on it.

A simple example is a picture of your deceased grandmother. Or a scarf she made for you by hand. Would you be comfortable destroying it? Of course that picture is not your grandmother and neither is the scarf, and you understand that perfectly well, but still these things hold sentimental value for you. You would not feel comfortable with their destruction or vandalism. This is what it means to sanctify the material and it is not the same thing as worship. They are the secular who worship the material and sell their very souls to acquire it; who value the picture and the scarf more than the people whom they may represent.

Humanities vs Sciences

The modern philosophical zeitgeist assumes that all truth is to be found in the material sciences alone. Citing a “Scientific Study” seems to be the primary method that people use to say “I know this is true because scientists said so”. Ironically, by doing so, science has become unscientific as they take the place of the new class of priests in modern society. But the lack of scientific consensus on the most basic topics should give us pause and make us realize that not all that is true can be measured and explained by the material sciences. In fact, science is a slower way of knowing things than by other methods such as inductive logic.

The scientific method is a fairly new way of asking and answering questions whereas there were many things that were known about the natural and spiritual world far before this method was codified and formalised. Roger Bacon understood the function of lenses and the refraction of light in this way in the 13th century. Medieval engineers understood how to build grand castles and fortresses of stone that would last centuries, without the use of modern technology or modern science.

More importantly, there were matters of the soul which the humanities answered and the sciences did not concern themselves with. This is still true today. Mainstream educational institutions have abdicated the humanities to the most evil ideologies imaginable--evil precisely because they begin their work by denying the existence of truth at all, this is post-modernism. When the humanities themselves have been corrupted and conquered, then society naturally suffers because ideas of right and wrong, virtue and vice, are polluted by bad ideas on every level. This leads to a society that punishes the innocent and rewards the evil. It cannot build anything beautiful and in fact condones the destruction of anything beautiful that has been built. Just look at the destruction of great works of art sanctioned by “climate change activists” and the horrendously de-spiriting architecture that vandalises modern skylines and ugly sculptures that defile cities.

The sacrilege persists not only in cities and educational institutions but also in people’s hearts as they destroy both their bodies and their souls under the malignant philosophy of modern day “arts” education. Even if you do not go out of your way to study history, art, or philosophy, the bad ideas still find you and inform your worldview if you do not aggressively seek out the truth.

I have written more about precisely why the humanities matter here.

Technology, whether it is analog or digital, is neither good nor evil on its own. I have written more about what makes technology good or evil here; whether it helps us live or helps us die.

In fact, digital technology can be the vehicle for great positivity and goodness in the world if it is used right. However, this right must be defined and that can only be done through the proper instruction of the humanities. They are the arts that will save society, not the sciences. Romanticism then, is also an understanding of the importance of the arts in restoring the human soul both to each individual and to mankind as a whole. The project of the restoration of the human soul is the project of the new romantic movement. And every time you seek to find the truth, to articulate virtue, to build something beautiful and good, you are a part of this movement.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to learn more about the Romantics and the Victorians, I have published in-depth guides on both movements here:

This is my Guide to the Victorian Era:

This is my Guide for Romanticism:

All of what you write is true. And yet, I'm not sure the answers we are looking for can all be found in the past. The contradictions of Christianity are what led us here in the first place after all. To go back to a Catholicism before the revelations of Darwin and post-modernism (which is not so much of a cancer as you seem to think, but rather primarily a critique of materialism and child-like faith in institutions (which I write about here (https://deusexvita.substack.com/p/in-defense-of-a-song-of-ice-and-fire) and here (https://deusexvita.substack.com/p/review-12-of-2024-infinite-jest), is not going to work, at least for me.

It's not that I haven't tried. I had a profound spiritual experience in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem in 2019, which led to my conversion in 2022. I still go to church every weekend, and to confession, and I think there is a lot of value in the Church, but the postmodernist critiques are kind of right? There is far too much doctrinal rigidity, at least in the American Catholic Church, far too little ecological awareness, and far too much emphasis on the elevation of humans over the rest of the biosphere. It doesn't have to be this way: genesis, the prophets and the gospels preach the virtue of humility and modest living time and time again, but even the priests at my parish (sworn to a vow of poverty) can't do without their cars, cellphones, and meat at every meal.

I think New Romanticism also holds some promise for me as well, but this also requires sacrifices few are willing to make. Being a romantic means connecting with nature in your life. It means giving up the digital and the material and living more humbly. Reading the Brother's K or Walden doesn't fundamentally mean much if you keep on consuming the way the rest of society does.

That said, change is slow, and we each have our own road to walk as we come into this Age of Aquarius. Keep up the good work!

Well done. The individual can strive for the material and spiritual. They are both part of our humanity. It is a paradox that we are created individuals and yet need each other to survive and thrive. I argue that the one who invents and produces the refrigerator by that action helps humankind to endure. Without that I would not be able to live. Reason and the spirit are not mutually exclusive. Once again you have enriched my day. Thanks.